Rock and Roll Is Back Again

How Stone and Roll Became White

And how the Rolling Stones, a ring in love with blackness music, helped lead the way to rock's segregated future.

Monitor Picture Library/Photoshot/Getty Images

This article is adapted from Just Around Midnight: Rock and Roll and the Racial Imagination.

In January of 1973—the same month that the Rolling Stones were banned from touring Nippon due to prior drug convictions, the same month that a ring called Kiss played its beginning gig in Queens, and the same month that a young New Jerseyan named Bruce Springsteen released his debut anthology on Columbia Records—Harper'due south magazine published an essay by time to come Pulitzer Prize winner Margo Jefferson titled "Ripping Off Blackness Music." The piece was partly a broad historical overview of white appropriations of blackness musical forms, from blackface minstrel pioneer T.D. Rice through the current day, and partly a more than personal lament over what Jefferson, a black critic, had come to see every bit an endless bicycle of cultural plunder. The commodity'due south most striking moment arrived in its penultimate paragraph:

The nighttime Jimi died I dreamed this was the latest stride in a plot being designed to eliminate blacks from stone music so that it may be recorded in history equally a cosmos of whites. Futurity generations, my dream ran, volition be taught that while rock may accept had its beginnings amongst blacks, it had its truthful flowering among whites. The best black artists will thus be studied every bit remarkable primitives who unconsciously foreshadowed future developments.

That Jefferson's "dream" came true is so obvious it seems self-evident. According to anthropologist Maureen Mahon, by the mid-1970s young black musicians who wanted to play songs past Led Zeppelin and Grand Funk Railroad recalled beingness ridiculed by white and black peers. In July 1979 thousands of white rock fans rioted at Chicago's Comiskey Park at the now legendary Disco Demolition Night, burning disco records in what many since take described as an anti-black, anti-gay, anti-woman, reactionary uprising. In 1985, Dorsum to the Futurity featured a climactic sequence in which history is altered and so that Chuck Berry'due south "sound" is retroactively invented by a Van Halen–obsessed white teenager. By 2011, when a popular New York "classic rock" radio station held a listener poll to determine the "Elevation 1,043" songs of all time, just 22—roughly 2 percent—were recordings by black artists, and 16 of those 22 were by the late Jimi Hendrix (the "Jimi" of Jefferson'due south dream), the alone black performer whose place in rock music hagiography is entirely secure.

Jefferson'south words were authentic, and it's tempting to telephone call them prophetic, but they weren't: Jefferson's nightmare had in fact come true before she wrote her article, fifty-fifty before "the night Jimi died." When Hendrix died in 1970, one prominent obituary pointedly described him as "a blackness man in the alien world of stone," and throughout Hendrix'due south tragically brief distinction the guitarist's race had been an ceaseless topic of fascination amongst fans of the music that had once been known as rock and ringlet. Even in the late 1960s, the exceptional nature of Hendrix'south race confirmed a view of rock music that was speedily rendering blackness definitively other, so much so that at the time of his death, the idea of a blackness man playing electric atomic number 82 guitar was literally remarkable—"alien"—in a way that would have been inconceivable for Chuck Berry just a curt while earlier.

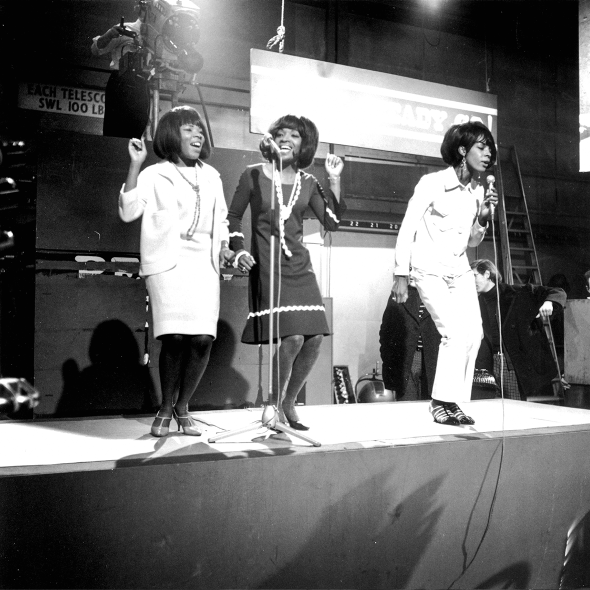

One thousand & M Ulf Kruger OHG/Redferns

How did rock-and-roll music—a genre rooted in blackness traditions, and many of whose earliest stars were blackness—come to be understood as the natural province of whites? And why did this happen during a decade generally understood to be marked past unprecedented levels of interracial aesthetic exchange, musical collaboration, and commercial crossover more broadly? Many of the near famous moments of 1960s music are marked past interracial fluidity: a young Bob Dylan's transformation of a 19th-century anti-slavery anthem, "No More Auction Block for Me," into the basis for "Blowin' in the Air current," a song that would get 1 of the most enduring musical works of the American ceremonious rights era; or the revolution of Motown Records, in which a black American entrepreneur bet against the racism of white America and won, and in doing so created the nearly successful black-owned business in the land. Or the previously unimaginable inundation of groups from England, about notably a quartet from Liverpool called the Beatles and a quintet from London called the Rolling Stones, both of whom were tireless evangelists for black American music and would soon hear their own songs performed, frequently, past the very musicians they once idolized. If, by the time of Hendrix'southward expiry, rock-and-scroll music had in fact "become white," how did this happen, and why?

* * *

Criticism, historiography, and pop discourse generally accept accepted a view of popular music in the 1960s equally divide according to genre and, more tacitly, race: on one hand is stone music, which is white; on the other, soul music, which is black. We hear Creedence Clearwater Revival's 1970 version of "I Heard It Through the Grapevine" every bit classic rock—the 662nd greatest archetype rock song of all time, co-ordinate to the aforementioned radio-station poll—and nosotros hear Marvin Gaye'southward slightly earlier version as something else, even though Gaye'due south version spent 7 weeks atop the charts in 1968 and 1969 and was far more popular in its day amidst white and black listeners. These divisions didn't happen as naturally equally we're often inclined to call up: They took work. Rock and roll became white in large part considering of stories people told themselves about it, stories that take come to construction the fashion we listen to an entire era of audio.

These stories have taken diverse and diffuse shapes, and the "whitening" of rock-and-roll music is a subject that has been approached by critics, historians, and commentators in a number of ways. 1 of these is casting the music's re-racialization as just 1 more iteration of a broad historical phenomenon of white-on-black cultural theft. In this telling, the performance of blackness music by artists ranging from Pat Boone to John Lennon to Janis Joplin is held as contiguous with a tradition of cultural plunder stretching at least as far dorsum as antebellum blackface minstrelsy. In its well-nigh reductive versions—the recurrent "Elvis stole rock and roll" accusation, for case—this formulation relies on hard-and-fast notions of cultural ownership and racial hermeticism, an ahistorical belief that there is a clear and definable boundary between black music and white music in America that is fundamentally impermeable. This belief does not agree up under bones scrutiny: All musicians are influenced by other musicians, and throughout American history most musicians worth hearing have been influenced past musicians whose skin is a different color than their own.

Another way that the whitening of rock-and-coil music has been addressed has been to identify the onus of separation on black performers by arguing that, every bit the 1960s progressed, black music finer self-segregated. In this narrative, the trajectory of black popular music is oftentimes directly linked to the trajectory of the civil rights movement, where rhetoric of self-determination and, in more farthermost cases, outright separatism became more than pronounced in the later on part of the decade. This is an intriguing argument with some amount of truth, simply it tends to conflate music and activism when the specifics of musicians' political commitments were oft hazier. The self-segregation narrative also excuses the majority (white) side for any responsibleness for the disappearance of black artists from stone music.

But by far the most common way that the whitening of stone-and-roll music has been discussed is simply not at all. The history of rock discourse is marked by a profound aversion toward discussions of race, and attempts to reckon the music'south racial exclusivity have frequently been met with hostility, peculiarly at the level of fandom. When Lester Bangs wrote an infamous comprehend story titled "The White Noise Supremacists" for the Village Voice in 1979 virtually the racism of New York'south punk and new moving ridge scenes, he was met with outrage and accusations of betrayal; when Sasha Frere-Jones wrote a similarly controversial slice for the New Yorker on the whiteness of indie stone in 2007, he was widely pilloried in the stone blogosphere. Neither of these essays are perfect works, but the dismissiveness and outright vitriol with which they were met speak to the extent of rock'south peculiar racial denialism.

In historiography this denialism conceals itself more subtly. In particular, there is a tendency toward stories of individual rock "genius" that foreclose discussions of race by jubilant individual artistry and intellect. While many black performers of the 1960s have been relegated to volume-length histories of black music mostly, white artists like Bob Dylan or the Beatles receive increasingly lavish biographies and isolated critical treatments of musical output. Recognizing white people every bit individuals while acknowledging nonwhite people but in relation to collectives is a hallmark of racism across all areas of culture: You could contend that the entire history of white supremacy rests upon it.

An alternative to this "Great Man" trend is a sort of cornball populism that glorifies stone-and-roll music for its democratizing "folk" elements. In these formulations rock music is often folded into a quasi-mythic lineage of American proletarian expression, with class trumping race in narratives that claim rock-and-roll music equally an inherently and nobly working-class grade. The fantasy of rock music as a fundamentally proletarian (and hence subtly raceless) genre has long haunted certain writing on the music. A perennial example of this is the case of Bruce Springsteen, a figure whose salt-of-the-globe persona has helped him carve out a niche every bit rock's "everyman." Springsteen'southward populist heroism is cited in terms of everything from his progressive politics to his geographical origins to his course background to his grueling performance way, all while his whiteness remains generally undiscussed.

AFP/Getty Images

And even so race and racial fantasy did reveal itself in Springsteen fandom, obliquely withal powerfully, after the 2011 death of his longtime saxophone player, Clarence Clemons, the lone blackness fellow member of the E Street Band. Eulogizing Clemons for the New Yorker, editor and Springsteen fan David Remnick described him as "a vessel of many great soul, gospel, and R&B players who came before him" and "an admittedly essential, and soulful, ingredient in both the sound of Springsteen and the spirit of the group." In this passage, language like "soulful ingredient" ascribes a sort of blackness musical magic to the effigy of Clemons, a magic in plow transferred to Springsteen past clan, through some mystical "spirit of the grouping." It'due south a move that subtly strips Clemons of agency ("a vessel") in order to enfold him into a fantastical rhetorical lineage—there is no real gospel saxophone tradition to speak of—that in turn confirms Springsteen'south white heroism. Clemons'due south presence (or, now, his absenteeism) affirms the axis of Springsteen'south whiteness while foreclosing give-and-take of racial inequality, rock music's equivalent of the "but some of my best friends … " argument.

The enormously powerful and enormously vague conceptual engine that powers all of the diverse omissions, fallacies, and obfuscations described above is authenticity. Rock credo is first and foremost an ideology of actuality: It delineates what constitutes "real" rock music, including who is authorized to play that music and who is authorized to listen to and talk nigh it. Since the 1960s playing and consuming rock music has offered new ways into beingness a "real" white person—most often a white man—and in many quarters being a white human being became a precondition for making "real" rock music.

The fact that this new make of musical whiteness and then depended on white performers' proximity to and fluency within black musical styles left blackness musicians themselves in a precarious position. Whereas artists similar Bob Dylan, the Rolling Stones, and Janis Joplin were lauded for casting off the shackles of racial conformity, artists similar those at Detroit's Motown Records, whose R&B-to-pop crossover formula was the most significant American musical achievement of the decade, were frequently derided for being insufficiently black. Equally the 1960s wore on, cosmopolitan versatility among black artists was not heard every bit identity transcendence but rather as racial expose, in accusations that were frequently lobbed past white critics. Again, perhaps the most tortuous example of this was Jimi Hendrix, who during his career was judged by many every bit a fraud or sellout, his black rendering his music as inauthentically stone at the same fourth dimension that his music rendered his person as inauthentically black. By dissimilarity, the very act of imaginatively engaging with historically black musical forms while keeping black bodies at arm's length became a newly powerful way of being white.

* * *

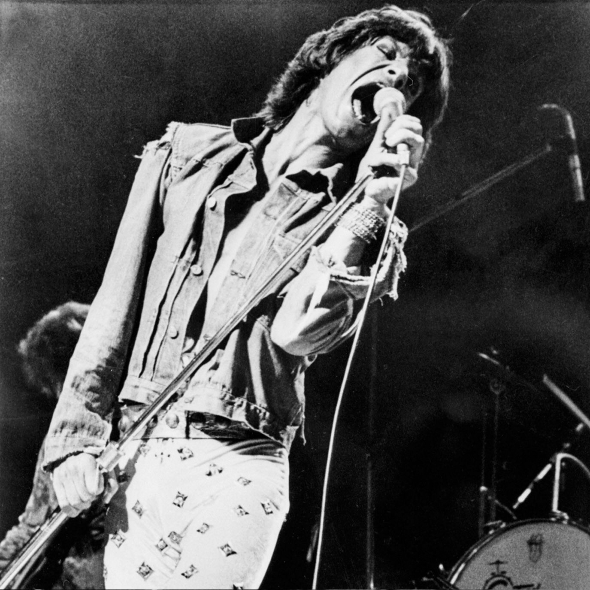

For an object lesson in the roiling, complicated, and speedily hardening racial realignment of rock music in the late 1960s, there are few better cases than the Rolling Stones. The ring's five-year run from 1968 to 1972—a period that opened with the career-reviving unmarried "Jumpin' Jack Wink" and lasted through their shambling, double-anthology masterpiece Exile on Main St.—is 1 of the bang-up sustained artistic peaks in all of popular music, and no rock band since has wielded more powerful and far-reaching influence over the music's self-formulation.

Crucial to the dominant mythology of the Rolling Stones throughout the 1960s was the band's purported connection to black and racial transgression, both in a musical sense and a more vague, imaginative 1. From their earliest coverage in both the British and American presses the Stones were characterized as harboring a preternatural fluency within blackness music and a prodigious knowledge of dejection and R&B traditions. 1 of the band's primeval Decca Records printing releases wrote of their "fanatic interest in R&B" and stated that the band learned their "uninhibited blues" from obsessive practise and "a record player on which they constantly played discs past artists similar Chuck Drupe, Bo Diddley, Little Walter and Jimmy Reed." The Rolling Stones were also described every bit a public menace, scourges to society, the embodiment of all the fears of generational overthrow and cultural disruption that the cuter and cuddlier Beatles had so effectively managed to sublimate.

Hysteria around the ring, particularly in their early, formative years, was keyed in barely veiled tones of racial threat. And yet as the 1960s progressed, the Rolling Stones' ongoing proximity to black music and musicians increasingly left them as outliers in a stone-music mural rapidly distancing itself from black people, their musical-cum–racial mixings farther validating the air of general transgression that the band and its handlers had long cultivated.

The Rolling Stones' relationship to black music, and to race itself, is among the most complex and controversial of any white artists in the history of rock and scroll. Over the long form of their stardom, the band has weathered accusations of minstrelsy, from Blackness Arts Movement poets and white academics alike. Yet for all of the long-continuing controversies over the ideals and particulars of the Rolling Stones' relationship to black music, the band was fiercely committed to a future for stone-and-curl music in which black music and musicians connected to matter, deeply. The Rolling Stones, a white British R&B band, presented a vision of the music obsessively rooted in tradition, and a black musical tradition specifically. Equally such they embraced a peculiar role of conservators of a musical past that they had borrowed past their own admission and doggedly tried to make their own.

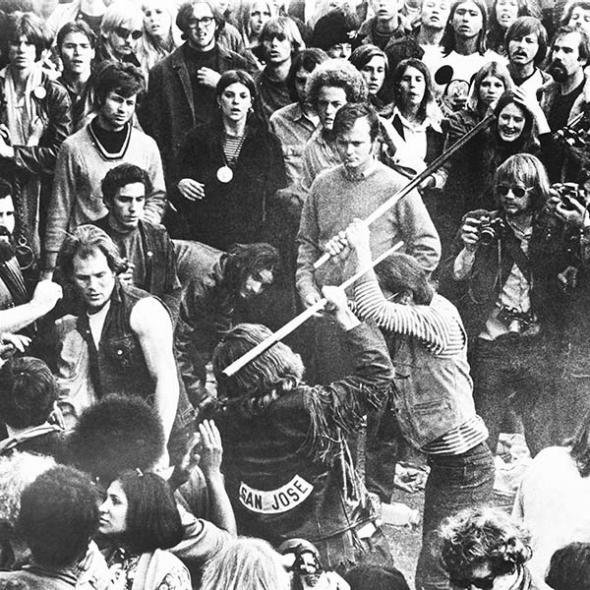

The Rolling Stones' paradoxically backward-looking avant-gardism was also marked by a fascination with violence, exemplified in songs such as "Jumpin' Jack Flash," "Sympathy for the Devil," "Street Fighting Man," "Gimme Shelter," and, most spectacularly and shockingly, "Dark-brown Carbohydrate." The Stones' experimentations with musical violence during this period were creatively invigorating merely ultimately brushed up against reality in catastrophic manner. The murder of Meredith Hunter at their costless concert in Altamont, California, in December of 1969 remains one of the more storied nightmares of the 1960s, and it irrevocably altered the band's position inside the public imagination.

Val Wilmer/Redferns/Getty Images

In the backwash of the 1960s the Stones would become arguably the archetypal rock band for all time, Jagger's and Richards' performance styles so naturalized that it would soon be notable when a rock star didn't sneer, slur, and strut. The Stones' obsession with black music and black musicians merely became role of the Rolling Stones, the band that wanted to be Muddy Waters now surrounded by a earth of rock musicians who wanted to be them. This transition—from the Rolling Stones being heard as a white band authenticated past their reverence for and fluency within black music, to the Rolling Stones only existence heard as a new sort of authentic themselves—is among the near significant turns in the history of rock.

* * *

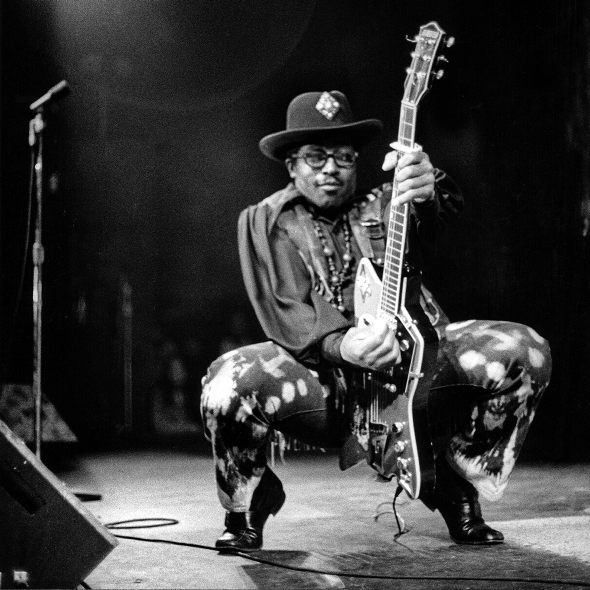

One of the many ironies of the Rolling Stones is that a band that has existed for more than fifty years and has been touring under the mantel of "the earth's greatest rock-and-roll band" for more than twoscore of them, never set out to be a stone-and-coil band at all. The Rolling Stones were born from the subcultural cauldron of British blues, an ersatz folk revival in which young British men developed obsessive relationships with black music and the doorway to mystical authenticity and escape from postwar British whiteness that it provided. Early printing coverage of the band went out of its way to emphasize that the grouping was strictly a blues or R&B band: "They are, they claim, first and foremost a rhythm-and-blues group," noted one 1963 contour. "If you lot refer to them equally a trounce outfit, they frown. If you venture to suggest that they play rock 'north' roll, they positively glower." From the outset of their careers in England, the Stones were linked to black music, always going out of their style to name-drop influences. Mick Jagger told Tune Maker in early on 1964, "Nosotros have always favoured the music of what nosotros consider the R&B greats—Muddy Waters, Jimmy Reed, and so on—and we would like to call up that nosotros are helping to give the fans of these artists what they want," and in an accompanying characteristic the balance of band listed its favorite artists as Reed, Waters, Chuck Berry, Bo Diddley, Ray Charles, and John Lee Hooker.

Robert Altman/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

To their credit the Rolling Stones did not take their own success as naïve testify of colorblindness amidst their fans and oft expressed frustration that their own performances of R&B were more pop among their countrymen than the original versions they and then revered. Some of the virtually pointed of these remarks came in an commodity written "by" the Stones for Melody Maker in 1964, when Jagger acknowledged that "it'south the system that'due south sometimes incorrect. Girl fans, peculiarly, would rather have a re-create by a British group than the original American version—mainly, I suppose, because they similar the British blokes' faces." Sexism aside, Jagger'southward suggestion that the fans "similar the British blokes' faces" implies that the singer recognized that the Stones' skin color had given them an undue advantage amidst audiences.

The Rolling Stones, particularly early, were many things—controversial, musically erratic, epitome-obsessed—but they did not avoid the topic of race or its salience to their ain commercial success. This may explain an underexplored aspect of the early career of the Rolling Stones: namely, the unusual enthusiasm with which the band was received by the black American press. In 1964 the Los Angeles Lookout called the group "wonderful" and wrote that "each [fellow member] has enough talent to take him well beyond the capabilities of the group." A cavalcade in the Chicago Defender wrote that "the Stones are worth everyone'southward attending. Many of us are agog R&B followers and believe me, the Stones are no less agog. They love and experience this music and if the coin was taken abroad, you lot would still observe them playing and singing R&B. … [T]he Stones are R&B men in the truest sense."

Such notices are more remarkable in low-cal of the fact that a big portion of white press attention directed at the band was scathing. In February of 1964, the Rolling Stones released their third single, a cover of Buddy Holly's "Not Fade Away;" it reached No. 3 on the U.K. singles charts and turned the group into total-fledged stars. That month also marked the first time that a author named Ray Coleman profiled the band for Melody Maker, and over the coming months no journalist would wield more influence in shaping media coverage of the band.

Coleman'southward near notorious slice of Melody Maker Stones coverage came in the March 14, 1964, issue, adorned with the headline "Would You Let Your Sis Go Out With a Rolling Stone?" The slice itself was fairly tame and by this indicate formulaic, each effort at generating controversy vague and suspiciously undersourced. There was a claim that "elders groan with horror at the Rolling Stones" to go forth with the rumored beingness of a letter from an unnamed fan whose parents had barred her from attending a Stones concert. The "Would Y'all Let Your" question would become iconic, though, appearing in various iterations in both the American and British presses, "sister" and "daughter" oft substituted interchangeably.

The scandal-driven discourse followed the band to the U.s.a.. When the Stones arrived in the United States in June of 1964 for their first American tour, the Chicago Tribune declared: "Thank you, Rolling Stones. You have been able to convince the world that no one, non even the Beatles, could be more repulsive than you lot." Huge swaths of American coverage focused on their physical appearance, specially their hair. The Los Angeles Times compared the band to cavemen, chimpanzees, and "very ugly Radcliffe girls." The New York Times ran 2 lengthy articles on "androgynous" hairstyles and reported that Cleveland, citing destructive effects on "the community's culture," would soon prohibit rock-and-roll performances at that urban center'due south Public Hall: "The ban goes into consequence afterwards tonight's Public Hall advent of the Rolling Stones, another group of shaggy-haired English singers."

A common aspect of most all the negative attention paid to the Rolling Stones past the American and British presses is the degree to which it traffics in the linguistic communication and imagery of racial threat. The obsessions with physical appearance, the dehumanizing comparisons to Neanderthals and animals, the vague moral phobia, the miscegenation implications distinctly embedded in the headline nearly sisters and daughters: All of these were ways of marking the Stones' appearance and foreignness equally indices of moral degeneracy and social danger. This is not to suggest that the Rolling Stones were rendered as black, only rather that they were rendered something other than properly white.

The Stones were seen as curiously obsessed with black American music and civilization to degrees most American youths were non, and this in turn was met by moral conservatism and xenophobia. The Beatles had encountered wary hostility in some corners, but the Stones were seen equally far more than dangerous. "Rolling Stones Lacking in Beatle-Like Finesse," declared the Washington Post in 1965, then went on to describe the band every bit "morbid and pathetic," even rendering Jagger's speech in dialect.

Every bit the Rolling Stones became more successful, this opprobrium continued to cling to them, and as the band shifted away from playing covers to playing mostly original material, their transgressive epitome and the content of their music grew more than and more intertwined. "(I Can't Get No) Satisfaction" and "Permit's Spend the Night Together" were censored or banned from radio and idiot box; "Female parent'southward Footling Helper" was ane of the earliest rock-and-roll hits about drug corruption; songs like "Get Off of My Cloud," "Nineteenth Nervous Breakdown," and "Paint It Black" were anthems of nonconformity.

Coming off a disastrous 1967 flirtation with psychedelia titled Their Satanic Majesties Request, in the leap of 1968 the Rolling Stones roared back onto the charts with "Jumpin' Jack Wink," a lean and gnashing work that was their all-time song since "Satisfaction." The song's lyrics were sparse and apocalyptic ("I was born in a crossfire hurricane/ and I howled at my ma in the drivin' pelting," was its opening couplet), similar some violent rebuttal to the receding Summer of Love. In late 1968 the band released Beggars Banquet, a work whose 10 songs presented the Stones in a land of renewed energy and versatility. Perhaps the album's most notorious rails was its opener, a half dozen-minute-plus opus titled "Sympathy for the Devil." "Sympathy" was essentially a tour through history guided by Match, one that began with the crucifixion, wound through the Russian revolution, and connected all the way upwards to the recent bump-off of Robert Kennedy.

"Sympathy for the Devil" furthered the notion of the Stones as diabolic and evil: When the Chicago Tribune ran an article on the rising of satanic imagery in stone music in September of 1968, the paper cited the band as central progenitors. The Washington Post described the group equally "satanic" and "demonic," while the New York Times shortly wrote that Jagger "combines bitterness, much hate, frustration, and defiance. … He adores his evil." The Stones' embrace of satanic imagery was itself, of class, partly inspired by the blues tradition, where songs about the devil constitute a robust subgenre, although this lineage was often left out of mainstream press coverage that sought to portray the band equally uniquely sinister. While the Stones had flirted with occult imagery earlier, "Sympathy for the Devil" raised this theme to new heights.

Concurrent to this fixation on the band's evilness was a growing association with the Rolling Stones and violence, fueled by the pb single from Beggars Feast, a raucous piece of music titled "Street Fighting Human being." "Street Fighting Man" was released as a single in late August 1968 and would reach No. 48 on the American charts, an impressively loftier showing given that, once again, many American radio stations refused to play it out of fears that it would be an incitement to violence. Released within a week of the 1968 Democratic National Convention into a summertime already thick with unrest on both sides of the Atlantic, its "picture show sleeve" boasted a graphic image of police force brutality taken from Los Angeles' Sunset Strip curfew riots of 1966. (The image was quickly withdrawn and would become a valuable collector's detail.)

"Street Fighting Man" was the follow-up unmarried to "Jumpin' Jack Wink" and was similar to its predecessor in energy and system. Information technology'due south an angry and relentless piece of music, a call to rebellion and an excoriation of conformity. "I remember the fourth dimension is right for a palace revolution/ but where I live the game to play is compromise solution," shouts Jagger in the song's second verse. Its lyrical content is pointedly vague, and there are no references to whatsoever specific political concerns; it'south an exploration of rebellion on its own terms, and with rapt attention to the traditions that preceded it. Most notably, the phrase "summer's here, and the time is right" is a direct homage to Martha and the Vandellas' 1964 Motown hit "Dancing in the Street," a song that had itself already been speculated as existence indirectly well-nigh urban unrest. "Street Fighting Man" took "Dancing in the Street" and made its allegorical insurgence far more than explicit, forcibly resituating the Vandellas and Motown into London, iv years later, a thoughtful and serious homage that imaginatively repurposes its object for a vastly different political context.

Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

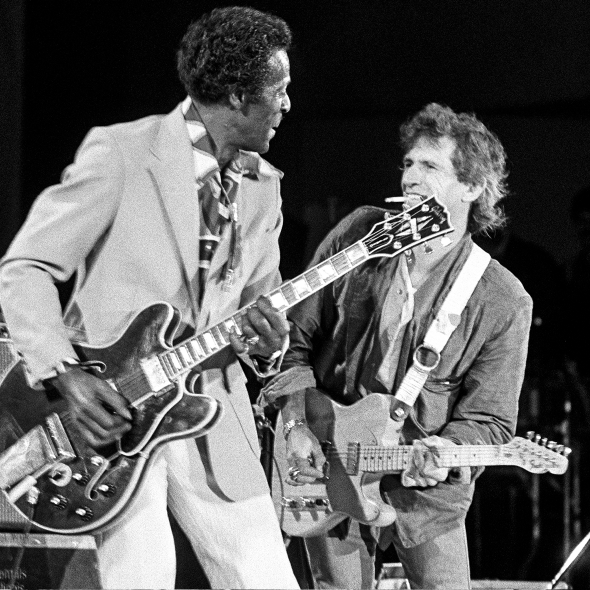

Here and elsewhere the Rolling Stones remained devoted to surrounding themselves with contemporary black music and black musicians in ways that were becoming increasingly uncommon in late 1960s rock. While the cultural mythology of Woodstock trumpets the notion of the festival equally a peaceful, multiracial utopia, the fact is that only ane band on the festival's lineup had spent whatever significant time on the R&B charts (Sly and the Family unit Stone), and the festival's remote location pointedly discouraged more urban demographics from attention. The Rolling Stones did non play Woodstock. The band'southward own 1969 tour boasted Ike and Tina Turner and B.B. Rex equally opening acts, and the band also often played alongside blackness performers onstage and in the studio, most notably singer Merry Clayton.

The Stones released their follow-up to Beggars Banquet, the evocatively titled LP Let It Drain, in tardily 1969. Its most striking moment was "Gimme Shelter," which found the Stones venturing even deeper into the dark recesses they'd explored in "Sympathy for the Devil" and "Street Fighting Human." It'southward an explicitly violent slice of music. The song begins with a quiet, tremolo-laden guitar intro, playing a straight-eighth-note figure that's little more than a decelerated version of the propulsive guitar introductions made famous by Chuck Berry in the 1950s on hits such equally "Roll over Beethoven" and "Johnny B. Goode." Subsequently the opening four bars of guitar introduction, more than instruments layer on. Low-cal percussion begins to creep through and a second guitar enters, playing sparse melodic fills. In the groundwork we hear vocals, the falsetto voices of Jagger and Richards singing wordless "oooohs" in a sort of occult rendering of street-corner doo-wop. After 8 more bars an electric bass enters, lightly plucking the root, and four confined later a piano crashes on the downbeat, striking an ominous octave in the low register. Charlie Watts cracks his snare twice, and the full band enters like an explosion into a quagmire.

The text of "Gimme Shelter" is an apocalyptic overflowing blues. The song reads like a hybrid of Delta bluesman Charley Patton's 1929 classic "High Water Everywhere" and William Butler Yeats' "The Second Coming," the lyrics' clarification of a "mad balderdash, lost its way" bearing singled-out echoes of Yeats's "rough creature" that "slouches towards Bethlehem to be born."

After the offset verse, "Gimme Shelter" enters its chorus. Here a 2d voice arrives, that of Merry Clayton, who belts the song'southward refrain in harmony with Jagger: "War, children/ It's just a shot away/ It'due south only a shot abroad." The chorus's utilization of "children" carries a double edge, invoking both the gospel tradition of referring to one's audition as "children" and late-1960s images of Vietnamese children slaughtered in villages and fleeing napalm strikes: children as victims of war, children as ourselves.

Perhaps the near indelible moment of "Gimme Shelter" comes after its second poetry and on the heels of a Richards guitar solo, when Clayton moves through four repetitions of the chorus, this time without the accompaniment of Jagger. The text shifts from "War, children/ It'due south but a shot away" to "Rape, murder/ It'due south just a shot away," and Clayton'south voice teeters between a song and a shout, producing the unsettling experience of hearing a woman repeatedly cry the word rape on a rock-and-roll record.

The song finds the Rolling Stones straying even deeper into musical history: the Chuck Berry intro, the knowing nods to various traditions such as flood blues, gospel, and doo-wop. Clayton'due south presence on the runway also heightens the notion of racialized violence surrounding the band, 5 white men and a black adult female in the recording studio, performing a song about rape and murder. "Gimme Shelter" remains 1 of the most iconic musical markers of violence in all of popular culture, appearing repeatedly in films, goggle box shows, and other media. Its power has long since exceeded the specifics of its original recording, however, due to its associations with a particular historical incident and the film that came out of information technology.

John Springer Collection/Corbis/Getty Images

On Dec. half dozen, 1969, the Rolling Stones arrived at the Altamont Speedway, located a picayune more than 50 miles east of San Francisco between the towns of Tracy and Livermore, to perform a gratuitous concert before a crowd estimated at 300,000 people. During their functioning of "Under My Thumb," a black teenager, Meredith Hunter, was stabbed to death by a Hells Angel, his murder captured on film by the crew of Gimme Shelter.

The Altamont tragedy and its aftermath seemed to fulfill an imaginative connection betwixt the Rolling Stones, racial transgression, and violence. Hunter'due south race—and his interest in an interracial human relationship—was mentioned incessantly in media accounts. The symbolic and tragic irony of Altamont was hard to ignore: a young black man, framed as an outsider, murdered at a rock concert at the end of the 1960s, a concert headlined by a white ring who had mined black musical traditions with unprecedented creative energy.

* * *

The Rolling Stones' insistence on the continued relevance of black music to rock and scroll was never fully heard; like Hendrix, they became exceptional figures, their curious obsessions with blues and R&B but becoming another manner of being white rock stars. The clattering R&B of "Jumpin' Jack Flash," the reworked Motown of "Street Fighting Human being," the tumultuous blues of "Gimme Shelter": Songs like these could be heard as whole musical histories, works whose lives depended on a continual and conscious interaction with the music that came before them, much of which was blackness in origin. The trouble was that the music the Stones were hearing equally both a living past and something yet present—"Summer'southward here, and the time is right"—was increasingly heard by its listeners solely as a past, and a distant 1. To rock audiences, black music and musicians were bathetic into a racial-cum-musical monolith, rapidly reimagined as the "remarkable primitives who unconsciously foreshadowed future developments" that Margo Jefferson wrote of in early on 1973.

Kirk West/Getty Images

For their part, the Rolling Stones were never entirely able to separate their relationship to blackness music from a fantastical fetishization of that music, a fetishization present from the band's beginnings. The roots of the band'due south dangerous, outsider image sprang from the conventionalities that for a white ring to play blackness music was a transgressive and titillating deed. The Rolling Stones themselves were by no means innocent in the structure of this image, and to no pocket-size caste it has lurked beneath the surface of nearly all of their work: Wait no further than the band's first post-Altamont hit, 1971's "Brown Sugar," a song about slave rape that'southward either the most outrageously subversive or outrageously offensive rock-and-ringlet vocal ever made (and quite mayhap both).

Merely the flirtations with violence that marked the music of the Rolling Stones in this period were also simply absorbed into rock ideology equally affirmations of the music's ain white authenticity, alchemized from iconoclasm into archetype. Instead of resounding every bit challengers to rock's hardening racial orthodoxy and increasingly overwhelming whiteness, the Rolling Stones were gradually recast as the original, the real, and—finally, and almost ironically—the Establishment. As stone continued into the 1970s an endless litany of bands fabricated the musical violence pioneered by the Stones during this period of relentless racial boundary-crossing into but some other marker of white male hegemony; this violence often served no political purpose and little imaginative purpose either. It simply became another fashion of being white, which was 1 thing that, for amend and worse, the Rolling Stones were never interested in being.

Adapted from Just Around Midnight by Jack Hamilton. Copyright © 2016 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. Used past permission. All rights reserved.

beaudoinsprinstif.blogspot.com

Source: https://slate.com/culture/2016/10/race-rock-and-the-rolling-stones-how-the-rock-and-roll-became-white.html

0 Response to "Rock and Roll Is Back Again"

Post a Comment